More Information

Submitted: December 05, 2025 | Approved: January 02, 2026 | Published: January 03, 2026

How to cite this article: Sehsah AM, Hafez KM, Attia MAA, El-Shennawy M. Diffusion Welding of Similar and Dissimilar Alloys: Review Article. Int J Phys Res Appl. 2026; 9(1): 001-011. Available from:

https://dx.doi.org/10.29328/journal.ijpra.1001141

DOI: 10.29328/journal.ijpra.1001141

Copyright license: © 2026 Sehsah AM, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is propeRLy cited.

Keywords: Vacuum diffusion welding; Dissimilar alloys; Microstructure evaluation; Mechanical analysis

Diffusion Welding of Similar and Dissimilar Alloys: Review Article

AM Sehsah1, KM Hafez1, Mohamed AA Attia2 and M El-Shennawy2*

1Manufacturing Technology Department, Welding Technology & NDT Lab., Central Metallurgical R&D Institute (CMRDI), Egypt

2Mechanical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Helwan University, Egypt

*Address for Correspondence: M El-Shennawy, Mechanical Engineering Department, Faculty of Engineering, Helwan University, Egypt, Email: [email protected]

Diffusion welding has emerged as a promising solid-state joining technique, particularly in applications where high heat input from fusion welding can introduce defects and negatively affect the properties of base materials. This process operates at lower temperatures than fusion welding, thereby preserving the mechanical properties of the joined materials. The success of diffusion welding relies on critical parameters such as temperature, pressure, time, and surface preparation. While it is an established method for joining similar alloys, its application to dissimilar alloys presents unique challenges, including differences in thermal expansion coefficients, melting points, and the potential formation of brittle intermetallic compounds. This review article aims to consolidate existing research on diffusion welding of similar and dissimilar alloys, providing a comprehensive understanding of the process and its parameters. Through critical analysis and evaluation of previous studies, the article proposes new inferences based on combined findings. It draws conclusions that will guide future experiments and applications, particularly in industries where precision and material integrity are paramount requirements, such as aerospace, automotive, and power generation. The application of diffusion welding as a reliable alternative to fusion welding highlights its potential to overcome the limitations of the high-heat-input process and enable successful joining of diverse/dissimilar material combinations.

Welding is a method of permanently joining metals, preventing them from being separated. With or without fillers, heat or external pressure, it is the most effective and cost-effective method for joining similar or dissimilar materials. Welding can be performed in a variety of environments, including outdoors, indoors, underwater, and even in outer space [1]. There are two main types of welding methods: Solid-State Welding (SSW) and fusion welding, both of which are used to join metals. Welding by fusion involves the fusion of parent materials at the connecting surfaces, along with filler materials, to form a weld bead. There are three types of welding in this category: gas welding, arc welding, and intense beam welding [2]. Various industries use these welding processes to manufacture automobile bodies, aircraft frames, boilers, pressure vessels, ships, tanks, and structural components, as well as to repair defects in both welded and cast products. It is important to note, however, that welding has drawbacks, including internal stresses and distortions in welded components, changes in microstructure, and exposure to hazards such as flashes, ultraviolet radiation, high temperatures, and fumes [3].

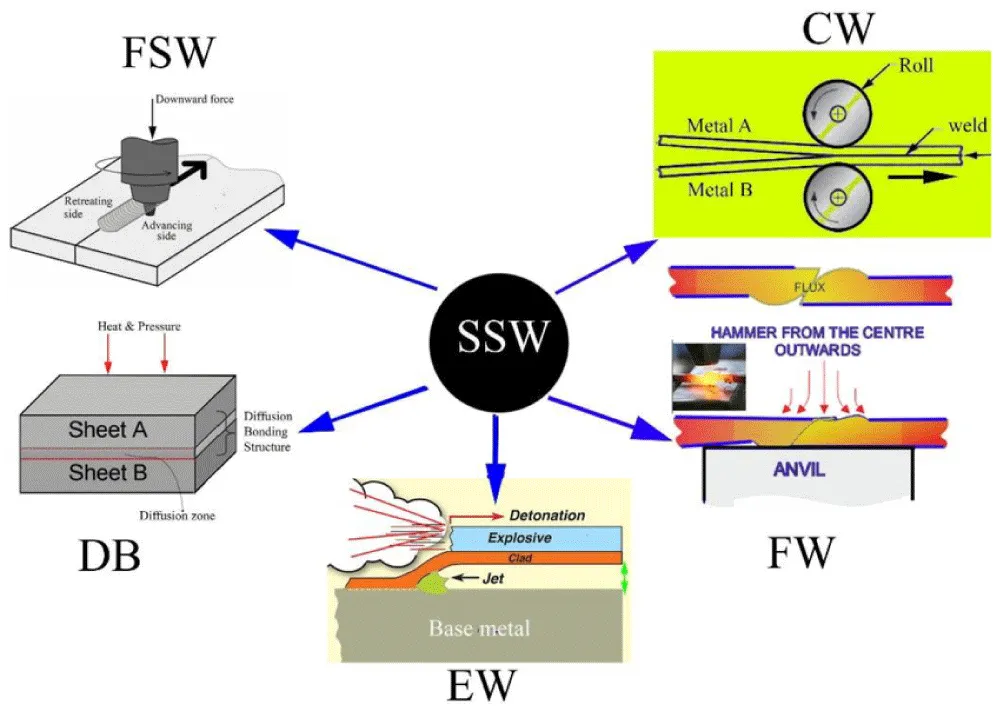

Several challenges are associated with welding dissimilar joints using traditional fusion rates. For example, filler metals should be selected based on their melting points, mechanical properties, and thermal expansion coefficients [4]. As a result of the formation of intermetallic compounds (ICs) during welding, metal joints may become brittle and have limited mutual solubility. Welding aluminum alloys with stainless steel, aluminum alloys with carbon steel, aluminum alloys with copper, copper alloys with titanium alloys, aluminum alloys with magnesium alloys, or tungsten-copper alloys with copper alloys presents particular challenges [5]. Researchers have extensively studied various fusion welding techniques for joining metals and creating multi-component assemblies. Fusion welding causes workplace air pollution, which poses significant health risks to workers and negatively impacts the environment through fumes and gas emissions [6,7]. Metal joining engineers face new challenges due to technological advances in missiles, rockets, nuclear energy, and electronics, particularly when working with dissimilar-metal joints. In certain specialized applications, traditional bonding techniques can be difficult to implement or fail to produce satisfactory bonds. Traditional fusion welding processes are facing significant challenges due to the increasing demand for higher productivity, efficiency, welding quality, and safety [8]. These challenges are not being addressed effectively by traditional welding processes as materials become more advanced an requiring specific properties. Solid-state welding (SSW) is a new technique that aims to meet evolving design requirements, adapt to advances in modern materials [9,10] and address the flaws and problems that accompany conventional welding techniques [11]. In solid-state welding (SSW) processes, no direct heat is applied. Most methods employ sufficient pressure to generate heat in the contact zone, but the resulting temperature typically falls below the melting point of the base materials [12]. Since there is no melting in SSW, the formation of intermetallic compounds (ICs) is minimized. Therefore, SSW is capable of joining dissimilar metals without any difficulty. It's possible that these processes won't consistently achieve the desired joint characteristics for specific applications [13]. Diffusion bonding (DB), friction stir welding (FSW), forge welding (FW), cold welding (CW), and explosive welding (EW) are the primary SSW techniques shown in Figure 1. This study analyzes the evolution of alloy microstructures utilizing solid-state welding techniques and reviews the most recent studies and developments in diffusion bonding (DB) for various alloy junctions.

Figure 1: The techniques that are commonly used for solid-state welding (SSW) [12].

Diffusion Bonding (DB)

Diffusion Bonding (DB) is a solid-state joining method that eliminates the need for a liquid interface, brazing, or the formation of cast products via melting and subsequent solidification [14]. DB creates a solid-state bond between similar or dissimilar materials by applying controlled pressure at temperatures below the materials' melting points. A vacuum or inert atmosphere is required as a nonoxidizing environment to avoid oxidation of the joining surfaces.

The DB process relies on solid-state diffusion, which produces a strong, superior bond by allowing atoms from the materials to mix progressively under high pressure and temperature. DB is a more dependable joining process than liquid-phase welding procedures because it successfully avoids problems such as cracking, deformation strains, flaws, and segregation [15]. The connections between bonding temperature, time, and applied pressure have been thoroughly examined in several studies [16]. The following is a description of the DB process using Fick's first law [17]:

D = D0e-Q/RT Where Q, Do, R, and D stand for the activation energy, frequency factor, gas constant, and diffusivity at temperature T, respectively.

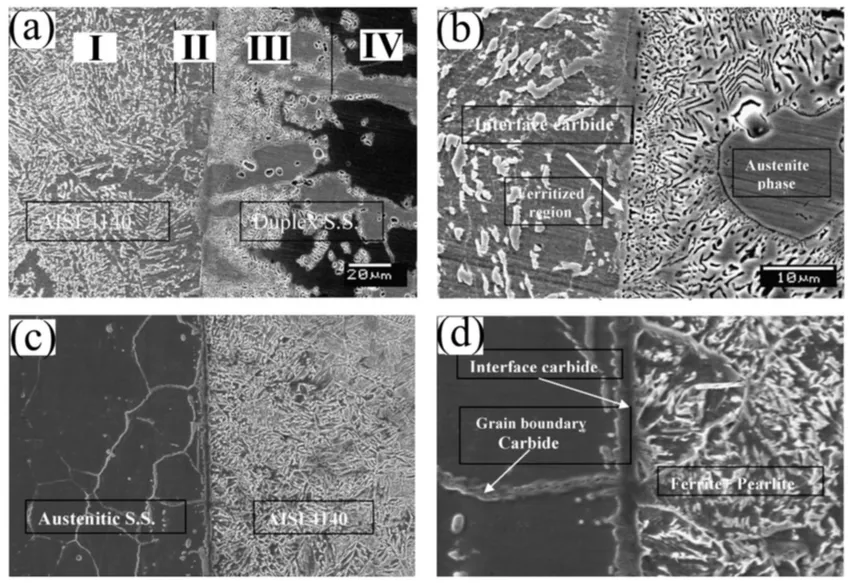

Duplex stainless steel is used in various industries, including paper and pulp, petrochemicals, gas and oil, and pollution control. Austenitic stainless steel is used in corrosive situations, but fusion welding can cause grain coarsening and solidification cracking. Duplex stainless steel welding eliminates the fused zone, making it suitable for alloys susceptible to segregation effects. Kurt's study on medium-carbon steel and austenitic and duplex stainless steel shows strong bonding. The microstructure of carbon steel AISI 4140 consists of ferrite-pearlite, ferrite-stabilized carbide network, and austenite-ferrite, with the other base metal, duplex stainless steel, also present in Figure 2 [14]. On the stainless-steel side, Figure 2b shows a layer of chromium carbide and a network of carbides—chromium-carbide forms around austenite grains in the ferrite phase of duplex stainless steel due to carbon diffusion. When cooled, carbon atoms form bonds with Cr, stabilizing cementite and ferrite [18]. Good bonding and the absence of micro-voids are observed in the interface microstructure of a bonded medium-carbon steel and austenitic stainless steel joint. The shear strength of austenitic stainless steel is influenced by chromium carbide that forms at grain boundaries and interface regions; the medium-carbon steel/austenitic stainless steel joint exhibits a wider interface carbide width.

Figure 2: The microstructure of the bonding interface of medium-carbon steel AISI 4140 with duplex stainless steel (a, b) and 304 austenitic stainless steel (c, d) shows a defect-free interface, a carbide network in the stainless-steel side and carbide in the interface bonding interface, and carbide forming on the interface [14].

Zhang, et al. investigated how bonding time affected the quality of the martensitic stainless-steel junction. It was discovered that the interface bonding ratio increases over time as the large voids in the bonding interface shrink [19]. Yu, et al. discovered that the DB duration and post-weld heat treatment consistently increased the interfacial bonding rate in diffusion-affected zones of high-Cr ferrite heat-resistant steel and TP347H austenitic heat-resistant steel [20]. Using a high-vacuum hot press on high-Cr ODS ferritic steel, Noh and Kasada studied solid-state DB and devolutions. Surface evolutions impact each of the three steps in the DB process. Prior to bonding, the first stage entails harsh surface deformation, which increases contact area and produces sealed pores [21].

Intimate contact between surfaces is created in the second step by deformation of the steel interface, which causes voids to vanish and early asperities to collapse. Clean, oxide-free surfaces create the best line-type bonding [21]. The last phase ultimately entails atomic diffusion at a steady temperature, and Derby's theoretical model [22] is consistent with this diffusion mechanism. This model found three potential processes for DB: (1) plastic deformation of surface asperities, (2) power law creep deformation of the surface, and (3) propagation of matter from bonded regions/interfacial void surfaces to increasing necks [21].

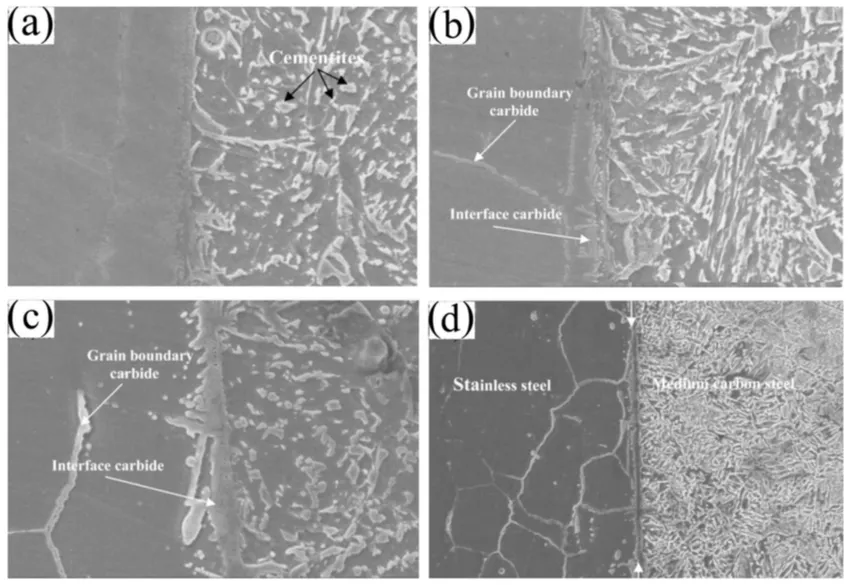

Kurt, et al. investigated how the bonding temperature affected the microstructural characteristics and shear strength of medium-carbon steel and austenitic stainless steel connection. All temperatures showed strong bonding, although at 750 °C, no discernible changes were observed. At 850 °C, martensite, partially spheroidized cementite, and chromium carbides were seen to develop in Figure 3 [23].

Figure 3: Microstructures of the joints' bonding interface between medium-carbon steel (AISI 4140) and austenitic stainless steel (AISI 304) at varying temperatures: 750 °C, 800 °C, 850 °C, and 900 °C, respectively [24].

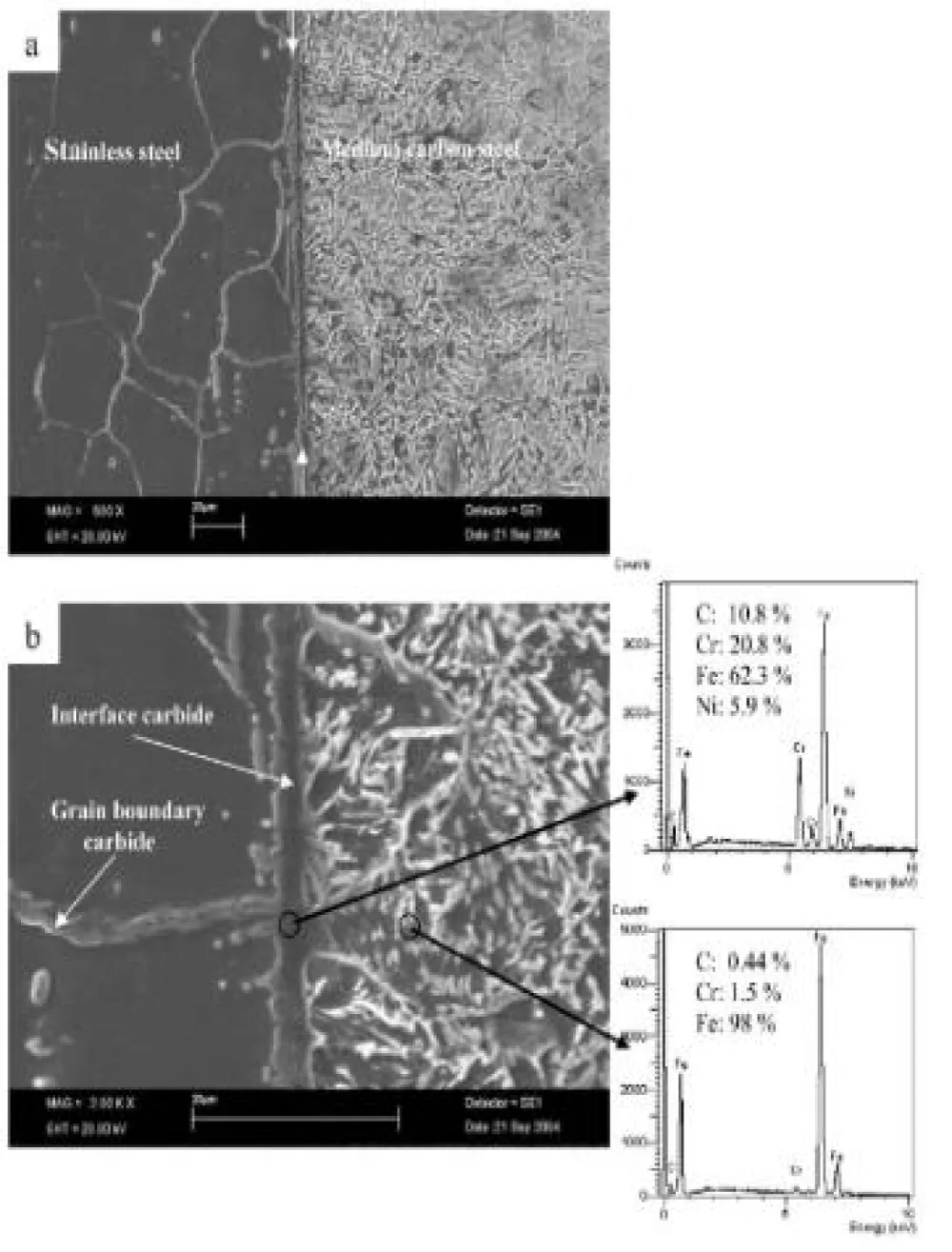

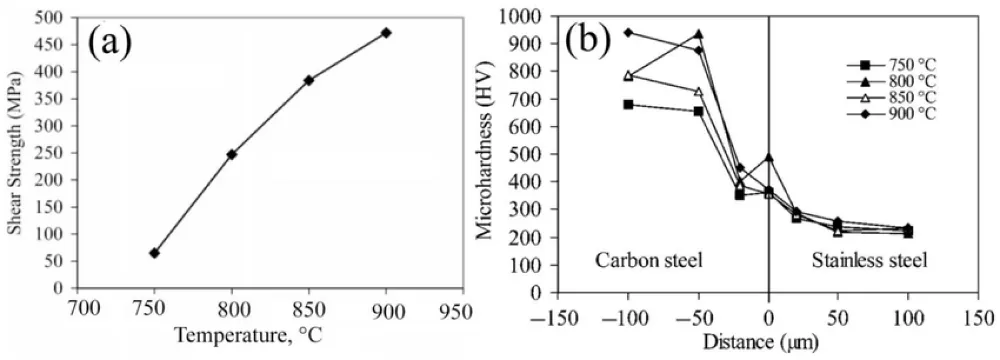

Grain barriers with chemistry containing 5.9 Ni, 10.8 C, 20.8 Cr, and 62.3 Fe are produced when C diffuses into stainless steel across grain boundaries, according to EDS analysis. Cr and Fe have a significant tendency to produce M3C9 carbides, as Figure 4 [23]. The impact of bonding temperature on the shear strength and hardness of the joints is shown in Figure 5. Because of the increasing mutual diffusion of the elements, the joint shear strength increased as the temperature rose, reaching its maximum value of 475 MPa at 900 °C (Figure 5a).

Figure 4: MSEM pictures of a specimen's bond contact that was bonded at 900 °C [23].

However, as shown by the micro hardness profiles (Figure 5b), the lack of marten site at the contact reduced the hardness at the interface zone between AISI 4140 and AISI 304 steel. As seen in Figure 5d, the diffused chromium is responsible for the hardness drop in the interface region of the carbon steel side at all temperatures. By creating a ferrite-stabilized zone, Cr prevents the production of marten site.

Figure 5: (a) The impact of bonding temperatures on the bonds' compressive shear strength and (b) the diffusion-bonded interface's micro hardness profiles [23].

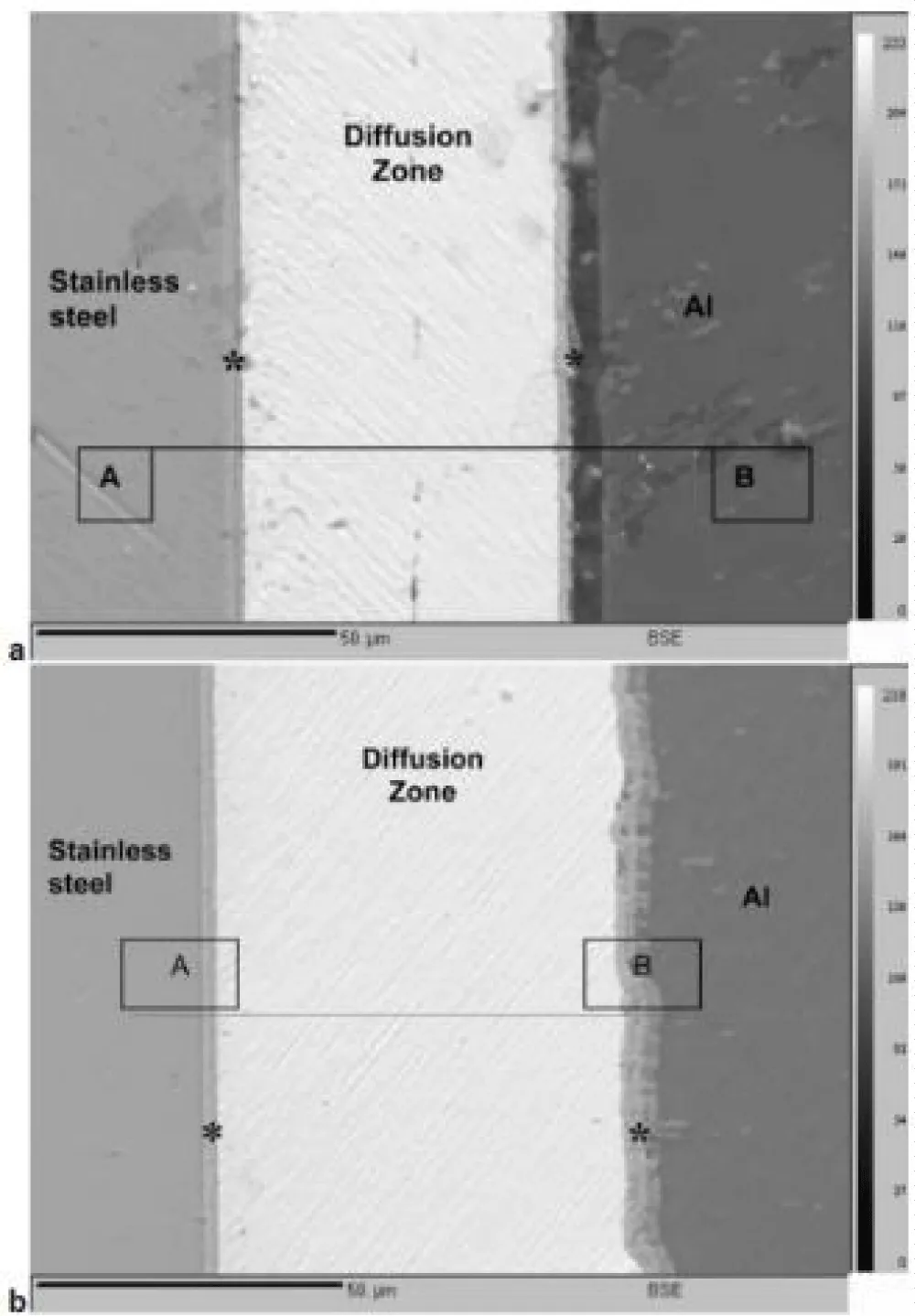

K. Bhanumarthy, et al. investigated the use of electrochemically deposited interlayers for diffusion welding aluminum alloys to stainless steel. They created three different geometries: tubular, cylindrical, and rectangular. All specimens, including tubular specimens, were adherent-coated use the gas pressure bonding approach. The microstructure of tubular specimens revealed irregular cavities and inadequate bonding at the Ag/Ag interface. Nonetheless, there were no holes or discontinuities in the bonding between the Al/Zn/Cu/Ag and SS/Ni/Cu/Ag interfaces, as shown in Figure 6 [24].

Figure 6: The position of the spot analysis by EPMA is shown by the asterisk in this backscattered electron image of tubular bonded specimens at 300 and 315 °C for four hours [24].

Effect of diffusion bonding parameters on microstructure and mechanical properties of the joint

Temperature effect: Bedjaoui state that higher temperatures generally enhance diffusion rates, improving bonding. For instance, welding aluminum to copper at temperatures between 425 °C and 525 °C resulted in multiple intermetallic phases, with increased hardness such as AlCu and Al3Cu4 [26] improved. In another study, temperatures from 500 °C to 600 °C showed that shear strength increased with temperature, peaking at 600 °C [27]. Using a Cu interlayer, Nader Nadermanesh, et al. investigated the diffusion bonding of 5083, 6061, and 7075 aluminum to AZ31 magnesium at 475 °C to 485 °C, noting deformation upon bonding [28].

Holding time effect: Saad, et al. concluded that extended holding times allow for greater diffusion, increasing interfacial bonding. For example, at 950 °C, holding times of 30 minutes resulted in incomplete bonding, while 45 minutes achieved optimal results with no interlayer gaps [29]. Aziz, et al. However, excessively long holding times can decrease shear strength due to the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds [30]. Specifically, prolonged holding times at elevated temperatures facilitate the diffusion of atoms across the interface, leading to the thickening of brittle intermetallic layers. Depending on the alloy system, excessive growth of brittle intermetallic compounds (IMCs) degrades shear strength and ductility. Common examples include Al-Cu (e.g., All2Cu, AlCu, Al3Cu4/Al4Cu9), Mg-Al (Al12Mg17 and Al3Mg2), and Al-steel (Fe2Al5 and FeAl3) may coarsen. These continuous brittle layers act as stress concentrators and preferred sites for crack initiation, which significantly deteriorates the joint's shear strength compared to joints bonded with optimized parameters.

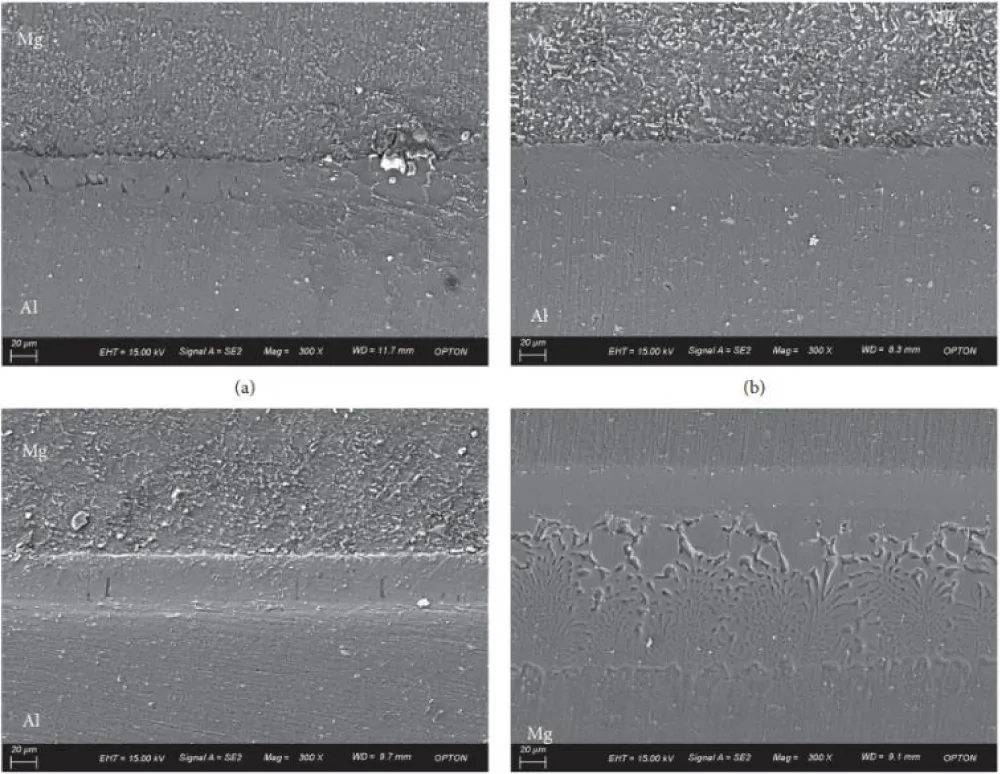

According to Ding's study on Mg/Al alloy diffusion bonding, the diffusion zone width increased with increasing annealing temperatures, with a noticeable change at 300 °C, as shown in Figure 7 [31].

Figure 7: The welded specimen's SEM image shows it (a) unannealed, (b) annealed at 200°C, (c) annealed at 250°C, and (d) annealed at 300°C.

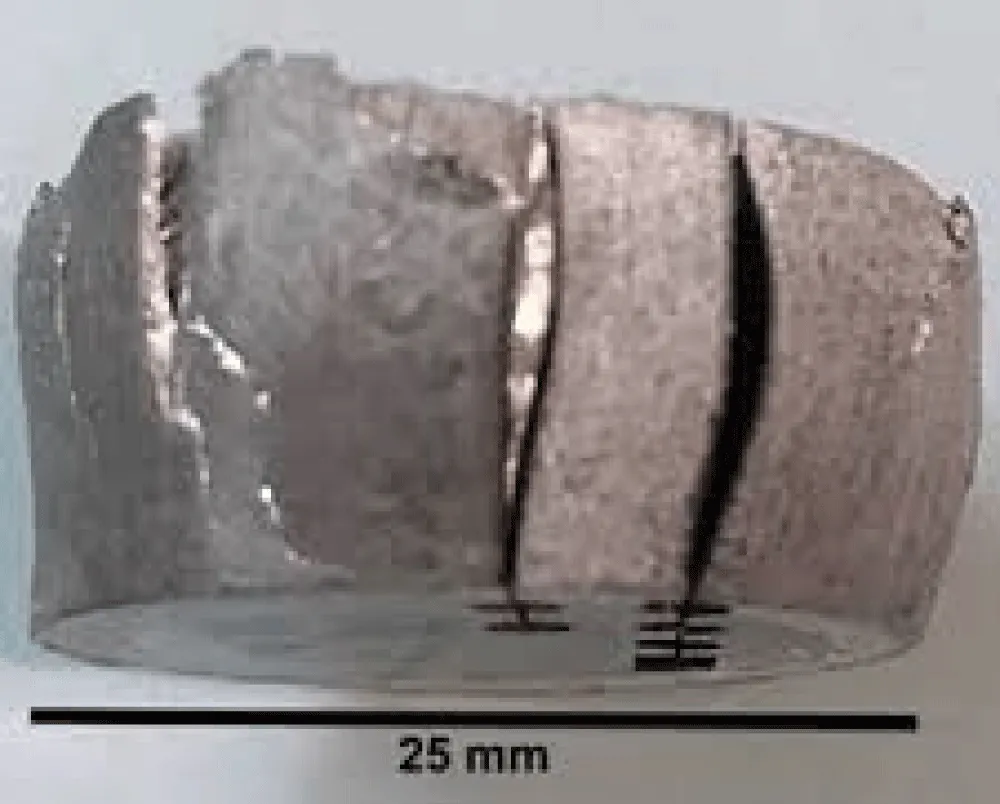

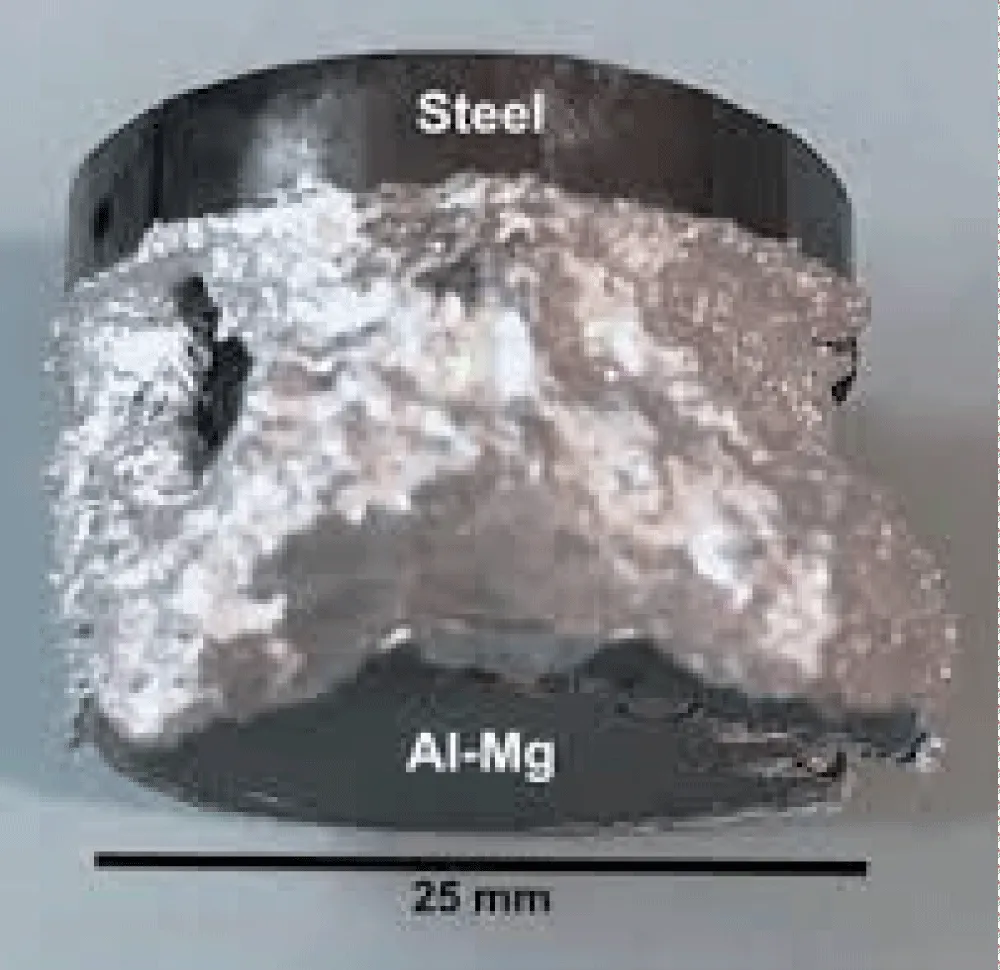

Zhang, et al. investigated how holding time affected a martensitic stainless steel joint's diffusion bonding. They discovered that as the duration of diffusion bonding grew, the spaces shrank and shrank [32,33]. Amir A. Shirzadi found that bonding aluminum and steel below 450 °C results in little to no response. The first bond was formed at 500 °C under vacuum and constant pressure. Most samples were heated at 60 °C per minute, cooled in a furnace, and vented when the temperature fell to 150 °C or less. However, samples bonded at 500 °C exhibited poor strength and broke down upon handling. The Al-Mg alloy decomposed and disintegrated at 550 °C or 560 °C, leading to a weak joint as shown in Figure 8 [34].

Figure 8: Al-Mg alloy disintegration at 560 °C during solid-state bonding to stainless steel. Despite employing a temperature around the Al-Mg alloy's melting point, virtually no bond formation took place [34].

Pressure effect: Samaritan, et al. investigated how pressure affected the mechanical characteristics and microstructure of a Ti-6Al-4V diffusion-bonded junction and found that, while the breadth of the bonded connection shrank with increasing pressure, its strength rose [35]. According to Elsa, et al. when bonding dissimilar Al/Cu, the strength increases with pressure because the intermetallic compound widens. For this reason, his research confirmed that the bonded joint's width increases with pressure. Additionally, increasing pressure causes the surfaces to become free of the oxide layer [36]. The diffusion depth at the Al/Cu interface rises in tandem with the bonding pressure. This is because the interfacial Al/Cu region's surface-to-surface contact is improved by increased pressure [36]. Kazako. Found that to guarantee close contact between the pieces' edges, the bonding pressure, also known as the pressing load, needs to be sufficiently strong. It should cover all of the gaps in the weld zone and sufficiently distort surface asperities. The joint may weaken if some holes remain unfilled due to inadequate pressure. Additionally, the pressing force facilitates the dispersion of oxide coatings, creating a cleaner surface that enhances diffusion and coalescence [37]. To prevent plastic deformation of the materials, the applied pressure must be lower than the material's yield strength at the elevated temperature [37]. Applying pressure in the 20–40 MPa range to stainless steel/Al joints results in plastic deformation; nevertheless, 10 MPa is the ideal pressure and yields the lowest aluminum yield strength at 450 °C, when excellent contact is observed [24]. According to Gopinath, et al., the dispersion of welded joints is strongly influenced by welding pressure, which also affects the microstructure, mechanical properties, and fracture behavior. Up to 6 MPa, higher pressure improves tensile and bulging characteristics [38]. Bond strength increasing the pressure during diffusion bonding. Bond strength is reduced in the absence of pressure. While thorough treatment can drastically lower bond strength under pressure, pressure lengthens bonds and enhances their strength [39]. Impulse pressure-assisted diffusion bonding (IPADB), which varies the pressure in diffusion bonding, shortens bonding durations and eliminates the need for thorough surface preparation, increasing process efficiency [40]. Increasing welding pressure in diffusion welding enhances joint strength in AlMg3/SiCp composites. Optimal pressure selection is crucial for successful diffusion bonding [41].

Surface finish effect: The effect of surface finish on diffusion welding is significant, influencing bond strength and quality across various materials. Research indicates that surface roughness can enhance diffusion bonding and strengthen joints.

Surface roughness and bond strength: Criado, et al. For AZ31 alloys, a roughness greater than 0.2 µm facilitates diffusion at lower temperatures and times, resulting in approximately 150% increases in bond strength compared to smooth surfaces [42]. In titanium alloys, a roughness ratio (X/R) below one leads to increased defects, whereas values above one yield defect-free joints, highlighting the critical balance between surface finish and weld quality [43].

Surface preparation techniques: The surface roughness of samples significantly affects the quality of diffusion bonding success, and welding improves joint quality [37]. Wei, et al. discovered that, when compared to surfaces treated with 400 or 800 grit emery paper, those polished with 1200 grit had the lowest roughness values for steel and aluminum [44]. The surface preparation before diffusion bonding results in the formation of both long and short-wavelength asperities [45]. Dr. Zeyad D. Kadhim states that joint strength decreases with increased roughness of the mating surfaces [32]. Ohashi and Hashimoto studied the impact of surface roughness on the bonding process and the weldability of diffusion welds on copper bars using different surface polishing techniques [46]. They also explored how surface roughness affects void formation and found that the primary mechanism for bond formation is creep deformation, influenced by bonding pressure, temperature, and time. They linked void elimination to the sintering mechanism [46]. Different surface finishing methods, such as grinding and sputter cleaning, significantly affect bond quality in aluminum alloys, with specific techniques yielding superior results [47]. The choice of surface finish also impacts the rate of interfacial void closure during bonding, with finer finishes generally promoting better outcomes [48]. While rougher surfaces can enhance bonding in some cases, excessive roughness may lead to defects, suggesting a need for optimization in surface preparation to achieve the best results in diffusion welding. Fitzpatrick, et al. investigated the diffusion bonding of aero components and emphasized the importance of smooth surfaces for effective contact in solid-state joining methods. They employed chemical machining techniques to ensure the smooth surface finish for diffusion bonding, achieving a standard surface roughness (Ra) of 0.8 to 1.0 µm. In contrast [49]. Shirzadi and Wallach employed a pre-bonding surface treatment to effectively bond super alloys and aluminum alloys [50,51]. Achieving diffusion bonding in aluminum alloys remains a persistent challenge due to the resilient oxide film on the substrate. This film acts as a diffusion barrier, impeding the formation of high-quality bonded joints [52]. When clean surfaces come into contact through interatomic forces, metals bond well. Disrupt the continuity of the oxide deposit during bonding to accomplish diffusion bonding in aluminum alloy [53]. Various methods have been explored to improve the bond quality of aluminum alloy and achieve robust bonded joints [53-58]. Different methods for diffusion bonding include applying pressure, transient liquid phase bonding with Zn or Cu, liquid gallium at room temperature, and solid-state bonding with Zn or Cu, which can cause macroscopic plastic deformation, uniform bonding, and brittle fractures [59,60].

The influence of the diffusion bonding temperature, holding time, and pressure on the shear strength of the joint at room temperature and high temperature

Influence of temperature: Venugopal, et al. concluded that higher bonding temperatures generally enhance shear strength by promoting diffusion and reducing defects. For instance, increasing the temperature from 490 °C to 520 °C improved bonding strength due to better particle dispersion [61]. Wei, et al. Conversely, lower temperatures (550 °C - 580 °C) with high pressure (30-40 MPa) can inhibit the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds, resulting in a shear strength of 181 MPa [44]. Gang Chen has studied the diffusion of AZ31 magnesium alloy and 5083 aluminum alloy at a temperature of 335 °C under pressure 4MPa for 120–480 min with an interlayer. He observed that the shear strength of the joint increased first and then decreased as the bonding time increased [62].

Effect of holding time: Wang, et al. Extended holding times can lead to the formation of brittle intermetallic compounds, reducing shear strength from 281 MPa at 30 minutes to 174 MPa at 60 minutes [63].

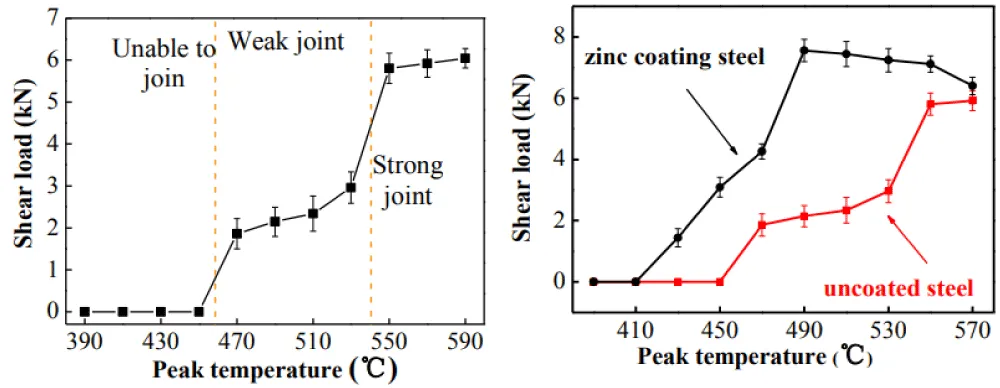

Role of pressure: Venugopal, et al. leading to improved shear strength. For example, higher pressures during bonding at elevated temperatures reduced defects and enhanced joint integrity [64]. While optimizing these parameters can significantly improve joint strength, excessive bonding time or temperature may lead to adverse effects, such as the formation of brittle phases, underscoring the need for careful process control. Yunlong Ding, et al. state that the annealing temperature of 250 °C of the diffusion process for dissimilar Mg/Al alloys is approximately near the recrystallization temperature of the joint, which gives more tensile strength in comparison with a temperature of 300 °C [31]. Kadhim, et al. have concluded that plastic deformation has a greater effect on joint strength [65]. Jian Lin, et al. studied the diffusion bonding of dissimilar zinc-coated steel, stainless steel, and aluminum by applying Gleeble simulation, mechanical testing, and microstructural characterization. They reported that increasing the bonding temperature increased joint strength, as shown in Figure 9a. Also, compared with aluminum, zinc-coated steel showed higher shear strength at 490 °C, as shown in Figure 9b [66].

Figure 9: (a) Relation between shear strength and peak temperature. (b): The relation between shear strength and zinc-coated and uncoated steel.

Negemiya, et al.'s study on diffusion bonding time in AISI 304 stainless steel joints and Ti6Al4V titanium alloy revealed that a 75-minute bonding duration enhances bonding and lap shear strength [67]. Venugopal, et al.'s study found that increasing temperature and pressure improves the bond strength of AA5083 aluminum alloy by reducing defects and enhancing secondary-phase particle dispersion [64]. Negemiya, et al. found a correlation between microstructure and bond strength in austenitic stainless steel (ASS)–titanium alloy joints, influenced by holding time [67]. Additionally, Suzuki, et al. utilized Joule heating diffusion bonding to join commercial-purity Ti to 304 stainless steel, revealing that the tensile strength of the joints correlated with the fraction of the well-bonded interface and inversely correlated with the thickness of intermetallic compound layers at the joint interface [68].

Failure mechanism of the joint: The failure mechanisms of diffusion bonding joints are complex and influenced by various microstructural factors. Key insights from recent studies reveal that microstructural features, such as grain boundaries and micro-voids, primarily govern crack initiation and propagation.

Crack initiation mechanisms: Zhang, et al. investigated interest in FGH96 joints; cracks initiate at the carbide/matrix interface due to strain mismatches, particularly at room temperature [69]. Li, et al. state that Intergranular cracks are predominant in 316L stainless steel joints, with favorable grain boundaries oriented at 0° to 20° to the loading axis being critical sites for crack initiation [70].

Role of micro-voids: Yujia and Shuxin have concluded that microvoids significantly influence interfacial failure. Still, they do not link until a substantial load is applied, indicating that microstructure plays a more crucial role than the voids themselves [71].

Influence of temperature and alloy composition: Jingqi, et al. that temperature affects the failure mechanism; at elevated temperatures, the role of carbides and grain boundaries diminishes, leading to cracks primarily along high-angle grain boundaries [72]. In cold-worked Alloy 600, premature brittle failures at the bond line were attributed to a lack of grain boundary diffusion, exacerbated by precipitates that hindered bond-line migration [73].

The influence of the interlayers on the microstructure and mechanical properties of the joint

The interface layer significantly influences the diffusion welding process by altering the microstructure and mechanical properties of the welded joints. The presence of interlayers, such as zinc or aluminum, can enhance bond strength and modify the diffusion characteristics at the interface.

Role of interlayers in diffusion welding

Intermetallic Compound Formation: The addition of a zinc interlayer in aluminum and stainless steel diffusion bonding led to the formation of complex intermetallic compounds, enhancing joint strength by 41.3% compared to joints without an interlayer [74]. Atomic Transfer: Interlayers facilitate atomic diffusion, which is crucial for bond formation. For instance, aluminum interlayers in titanium-stainless steel bonding improved bond strength through optimized atomic transfer [75].

Influence of welding conditions

While interlayers generally improve diffusion-bonding outcomes, their effectiveness can depend on specific welding parameters and material combinations, suggesting a nuanced approach to optimizing diffusion-bonding processes. Enes Akca, et al. state that Interlayers have become increasingly valuable in diffusion welding applications. While they offer advantages in improving joint quality, an improperly selected interlayer can significant intermetallics at the weld interface and enhancing compatibility when joining dissimilar metals [76]. Kundu has used copper and nickel interlay. Kundu successfully bonded Ti to 304 stainless steel through diffusion welding. Experimental results showed that samples bonded with the copper interlayer achieved a strength of 318 MPa, whereas those bonded with the nickel interlayer reached 302 MPa [77]. Using copper and silver interlayers, Berrana examined the diffusion bonding of titanium and aluminum at 750 °C and 3 MPa pressure for 10 and 60 minutes. After 60 minutes, the maximum hardness was reached at 750 °C. In a different study [78]. Berrana and Zhang studied the bonding of Ti-6Al-4V and stainless steel using silver and nickel interlayers in diffusion welding. Silver interlayers were found to be the most effective, with the best bonding observed at 850 °C for 30 minutes. Nickel interlayers minimized the presence of brittle and hard compounds [79]. Commercially pure titanium was subjected to diffusion bonding by Rahman and Cavalli [80], both with and without interlayers of copper and silver. Without an interlayer, the highest tensile strengths were 382 MPa, 502 MPa with Cu, and 160 MPa with Ag.

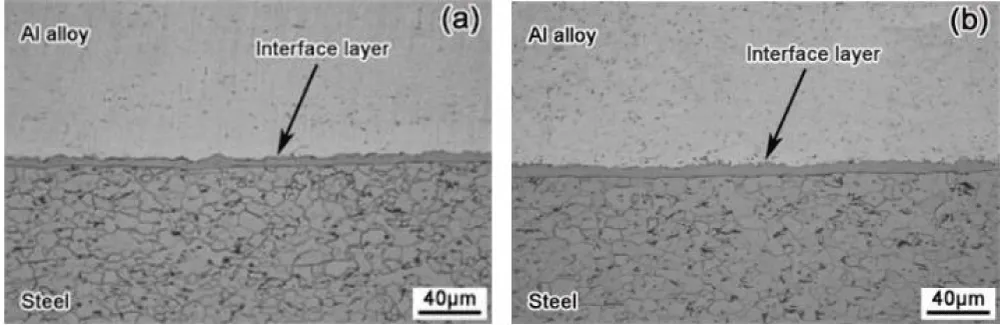

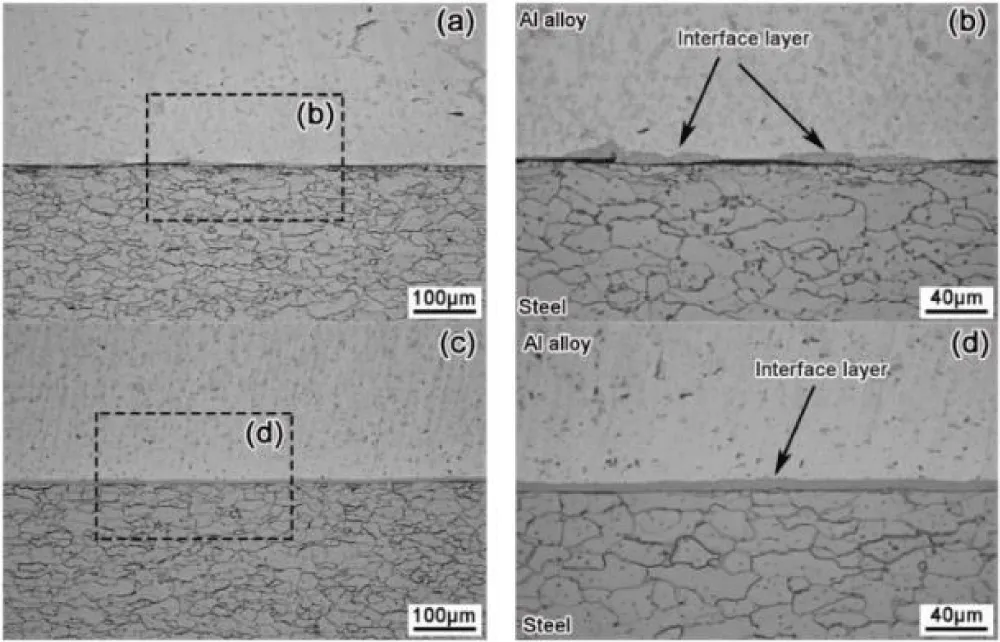

As shown in Figure 10, the observed growth of the thick layer due to the zinc coating layer formed a continuous and smooth interface layer at a diffusion temperature of 510 °C in comparison of discontinuous and thin interface layers of uncoated steel, as shown in Figure 11, the formation of a thick interface layer of zinc improves the shear strength of the joint, also increasing the temperature to 550 °C This leads to an increased thickness of the interface layer, as shown in Figure 10b [81].

Figure 10: The way the zinc-coated steel and aluminum interface layer looks at (a) 510 °C and (b) 550 °C [81].

Figure 11: The interface layer between aluminum and uncoated steel materials was observed at varying temperatures, including (a) 510 °C, (b) 510 °C local amplified, (c) 550 °C local amplified, and (d) 550 °C local amplified [81].

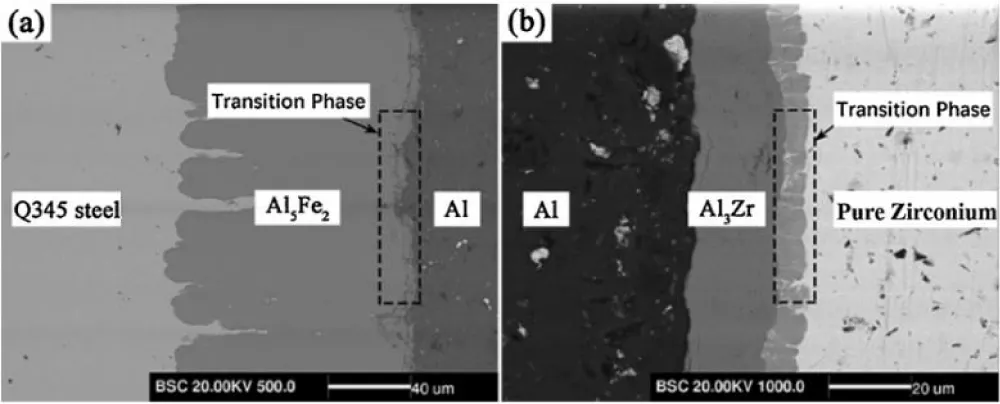

Yang, et al. have studied the effect of pure aluminum foil as an interlayer for bonding steel Q345 to pure zirconium. They stated that some phases formed at the interface between the aluminum layers Al5Fe2 and Al3Zr and found that the hardness of Al5Fe2 is much higher than that of Al3Zr, which led to the brittleness of the thin layer and its fracture. They also stated that the thickness of the transition phases increases with temperature, as shown in the microstructure in Figure 12 [82].

Figure 12: A high magnification SEM image of the RLs, (a) Al5Fe2/Al interface and (b) Al3Zr/Zr interface [82].

Applications involving diffusion bonding are increasingly benefiting from the interlayer. By choosing the right kind and composition the contact surfaces could be improved, interfacial intermetallic compounds could be avoided, and the melting point could be lowered [83].

Hirose, et al. used diffusion bonding to combine different aluminum alloys with steels. According to their research, when Al-5000 aluminum-magnesium alloys are bonded to steel, the reaction layers in these alloys grow much more rapidly than those in Al-6000 alloys. Consequently, the high magnesium (Mg) concentration caused the reaction layer to expand quickly and irregularly, resulting in noticeably weak joints between Al-Mg and steel. The scientists also noted that many samples broke during machining of the tensile test specimens, making it impossible to determine the joint strength [84].

Furthermore, Hirose, et al. examined how magnesium content affected the interfacial reaction in diffusion-bonded aluminum-steel junctions. According to their research, the magnesium concentration should be kept below 1.0 weight percent to achieve acceptable binding strength [85].

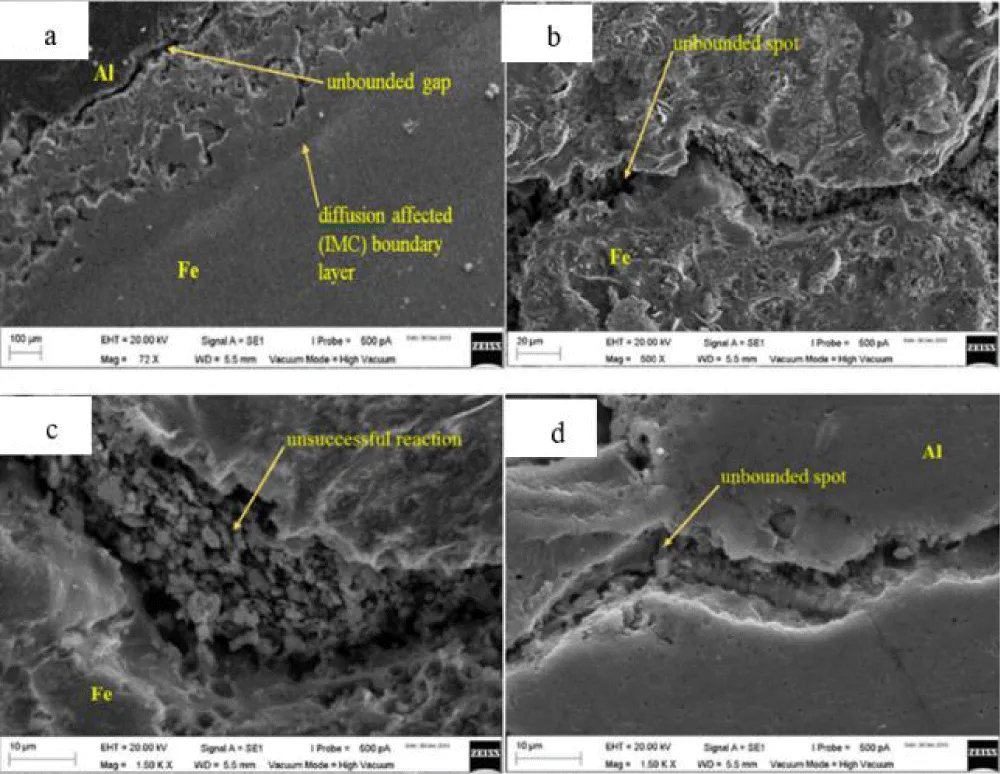

In the dissimilar bonding of Al-Fe, Ismail, et al. have proven that the presence of gallium does not affect the bond's strength. As shown in Figure 13, the microstructure exhibits gaps and holes due to inadequate pressure.

Figure 13: Shows Al-Fe joint topography at various magnifications, including (a) 72, (b) 500, (c) 1500, and (d) 1500 magnifications, using SEM.

Gallium was added to magnesium oxide on Al-Mg surfaces to improve bonding. However, every sample broke during handling or machining. Two samples used more liquid gallium at the joint surfaces, bonding at temperatures of 540 °C and above. As shown in Figure 14, the Al-Mg alloy melted suddenly, halting the bonding process [34].

Figure 14: The abrupt melting of the Al-Mg alloy as a result of the surface migration of magnesium and subsequent eutectic interaction with liquid gallium [34].

According to Wu, et al., using pure aluminum as an interlayer in assisted diffusion bonding for both the 1420 Al-Li alloy and the diffusion bonding of 1420 Al-Li alloy and 7B04 Al alloy could result in a strong bonded junction. Concentration gradients of alloying elements aid diffusion, increasing diffusion fluxes and improving interface integrity.

Shirzadi and associates investigated the use of titanium interlayers for welding dissimilar junctions between stainless steel and aluminum alloy. Because magnesium oxide is stable and has little chemical affinity, they did not detect any reaction. Because there was not enough liquid Al-Cu eutectic, the transient liquid phase bonding failed.

Diffusion welding is a versatile and effective method for joining alloys, offering strong and durable bonds when properly executed. The success of the process depends on careful control of temperature, pressure, and time, as well as effective management of surface conditions. While challenges such as oxide films and dissimilar-material bonding persist, ongoing advancements in surface treatments, process control, and materials science are paving the way for improved diffusion-welding practices. Continued research and technological innovation will further enhance the capabilities and applications of this essential joining technique.

- Wu D, Zhang P, Yu Z, Gao Y, Zhang H, Chen H, Chen S, Tian Y. Progress and perspectives of in-situ optical monitoring in laser beam welding: Sensing, characterization and modeling. J Manuf Process. 2022;75:767–791. Available from: https://research.lancaster-university.uk/en/publications/progress-and-perspectives-of-in-situ-optical-monitoring-in-laser-/

- Vaishnavan SS, Jayakumar K. Tungsten inert gas welding of two aluminum alloys using filler rods containing scandium: The role of process parameters. Mater Manuf Process. 2021;37:143–150. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/10426914.2021.1948055

- Singh DK, Sharma V, Basu R, Eskandari M. Understanding the effect of weld parameters on the microstructures and mechanical properties in dissimilar steel welds. Procedia Manuf. 2019;35:986–991. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2019.06.046

- Harada Y, Sada Y, Kumai S. Dissimilar joining of AA2024 aluminum studs and AZ80 magnesium plates by high-speed solid-state welding. J Mater Process Technol. 2014;214:477–484. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2013.10.005

- Sridharan N, Isheim D, Seidman D, Babu S. Colossal super saturation of oxygen at the iron-aluminum interfaces fabricated using solid state welding. Scr Mater. 2017;130:196–199. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scriptamat.2016.11.040

- Golbabaei F, Khadem M. Air pollution in welding processes—Assessment and control methods. Curr Air Qual Issues. 2015:33–63. Available from: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/48086

- Popović O, Prokić-Cvetković R, Burzić M, Lukić U, Beljić B. Fume and gas emission during arc welding: Hazards and recommendations. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2014;37:509–516. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.05.076

- Zhan M, Guo K, Yang H. Advances and trends in plastic forming technologies for welded tubes. Chin J Aeronaut. 2016;29:305–315. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cja.2015.10.011

- Akca E, Gürsel A. Solid state welding and application in the aeronautical industry. Period Eng Nat Sci. 2016;4:1–8. Available from: https://doi.org/10.21533/pen.v4i1.46

- Nassiri A, Abke T, Daehn G. Investigation of melting phenomena in solid-state welding processes. Scr Mater. 2019;168:61–66. Available from: https://www.scinapse.io/papers/2942789837

- Yildirim S, Kelestemur MH. A study on the solid-state welding of boron-doped Ni3Al–AISI 304 stainless steel couple. Mater Lett. 2005;59:1134–1137. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2004.08.042

- Khedr M, Hamada A, Järvenpää A, Elkatatny S, Abd-Elaziem W. Review on the solid-state welding of steels: diffusion bonding and friction stir welding processes. Metals. 2022;13(1):54. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/met13010054

- Aleem HAA. Study on bonding of dissimilar metals by ultrasonic bonding and materials evaluation of the bonds [dissertation]. Kitakyushu (Japan): Kyushu Institute of Technology; 2004.

- Kurt B. The interface morphology of diffusion-bonded dissimilar stainless steel and medium carbon steel couples. J Mater Process Technol. 2007;190:138–141. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2007.03.063

- Yılmaz O. Effect of welding parameters on diffusion bonding of type 304 stainless steel–copper bimetal. Mater Sci Technol. 2001;17:989–994. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1179/026708301101510834?urlappend=%3Futm_source%3Dresearchgate.net%26utm_medium%3Darticle

- Li P, Wang L, Yan S, Meng M, Xue K. Temperature effect on the diffusion welding process and mechanism of B2–O interface in the Ti2AlNb-based alloy: A molecular dynamics simulation. Vacuum. 2020;173:109118. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacuum.2019.109118

- AlHazaa A, Haneklaus N. Diffusion bonding and transient liquid phase (TLP) bonding of type 304 and 316 austenitic stainless steel—A review of similar and dissimilar material joints. Metals. 2020;10:613. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/met10050613

- Kim SJ, Lee CG, Lee TH, Oh CS. Effect of Cu, Cr, and Ni on mechanical properties of 0.15 wt.% C TRIP-aided cold rolled steels. Scr Mater. 2003;48:539–544. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6462(02)00477-3

- Zhang C, Li H, Li M. Formation mechanisms of high-quality diffusion-bonded martensitic stainless steel joints. Sci Technol Weld Join. 2015;20:115–122. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1179/1362171814Y.0000000258?urlappend=%3Futm_source%3Dresearchgate.net%26utm_medium%3Darticle

- Noh S, Kasada R, Kimura A. Solid-state diffusion bonding of high-Cr ODS ferritic steel. Acta Mater. 2011;59:3196–3204. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2011.01.059

- Shi Y, Liu J, Yan Y, Xia Z, Lei Y, Guo F, Li X. Creep properties of composite solders reinforced with nano- and microsized particles. J Electron Mater. 2008;37:507–514.

- Hull D, Rimmer D. The growth of grain-boundary voids under stress. Philos Mag. 1959;4:673–687. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1080/14786435908243264

- Kurt B, Orhan N, Ozel S. Interface microstructure of diffusion-bonded austenitic stainless steel and medium carbon steel couple. Sci Technol Weld Join. 2007;12:197–201. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1179/174329307X175164

- Bhanumurthy K, Fotedar RK, Joyson D, Kale GB, Pappachan AL, Grover AK, Krishnan J. Development of tubular transition joints of aluminium/stainless steel by deformation diffusion bonding. Mater Sci Technol. 2006;22(3):321–330. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1179/026708306X81522

- Chen G, Tan T, Guo Y, Wang H, Liu Y, Pan H. An investigation on diffusion bonding of Mg/Al dissimilar metals using Zn-Bi alloy as interlayer. Mater Lett. 2023;349:134827. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2023.134827

- Bedjaoui W, Boumerzoug Z, Delaunois F. Solid-state diffusion welding of commercial aluminum alloy with pure copper. Int J Automot Mech Eng. 2022;19(2). Available from: https://doi.org/10.15282/ijame.19.2.2022.09.0751

- Safarzadeh A, Paidar M, Youzbashi-Zade H. A study on the effects of bonding temperature and holding time on mechanical and metallurgical properties of Al–Cu dissimilar joining by DFW. Trans Indian Inst Met. 2017. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12666-016-0867-y

- Nadermanesh N, Azizi A, Manafi S. Mechanical and microstructure property evaluation of diffusion bonding of 5083, 6061, and 7075 aluminium to AZ31 magnesium using Cu interlayer. Proc Inst Mech Eng B J Eng Manuf. 2021;235(13):2118–2131. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1177/09544054211014489

- Saad AJ, Triyono T, Agus S, Supriyanto N, Muhayat, Yuliadi Z. Effect of holding time on the diffusion behavior at the interface of dissimilar metals joint between aluminum and carbon steel joint using element promoter. Mod Appl Sci. 2014;8(5):1–?. Available from: https://doi.org/10.5539/mas.v8n5p1

- Azizi A, Alimardan H. Effect of welding temperature and duration on properties of 7075 Al to AZ31B Mg diffusion bonded joint. Trans Nonferrous Met Soc China. 2016. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1003-6326(16)64091-8

- Ding Y, Zhang S, Wu B, Hao J. Sequential process of diffusion bonding and annealing on dissimilar welding of Mg/Al alloys. Adv Mater Sci Eng. 2021;2021:6691422. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6691422

- Kadhim ZD, Al-Azzawi AI, Al-Janabi SJ. Effect of the diffusion bonding conditions on joints strength. J Eng Sustain Dev. 2009;13(1):179–188. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337209506_Effect_of_the_Diffusion_Bonding_Conditions_on_Joints_Strength

- Zhang C, Li H, Li M. Formation mechanisms of high-quality diffusion bonding martensitic stainless joints. Sci Technol Weld Join. 2015;20:115–122. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1179/1362171814Y.0000000258?urlappend=%3Futm_source%3Dresearchgate.net%26utm_medium%3Darticle

- Shirzadi AA, Zhang C, Mughal MZ, Xia P. Challenges and latest developments in diffusion bonding of high-magnesium aluminium alloy (Al-5056/Al-5A06) to stainless steels. Metals. 2022;12(7):1193. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/met12071193

- Samavatian M, Zakipour S, Paidar M. Effect of bonding pressure on microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti-6Al-4V diffusion-bonded joint. Weld World. 2017;61:69–74.

- Elsa M, Khorram A, Ojo OO, Paidar M. Effect of bonding pressure on microstructure and mechanical properties of aluminium/copper diffusion-bonded joint. Sadhana. 2019;44:1–9. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12046-019-1103-3

- Kazakov VN. Diffusion bonding of materials. Oxford: Pergamon Press; 1985;157–170. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/edited-volume/9780080325507/diffusion-bonding-of-materials

- Thirunavukarasu G, Murugan B, Chatterjee S, Kundu S. Influence of welding pressure on diffusion welded joints using an interlayer. Weld J. 2017. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Influence-of-Welding-Pressure-on-Diffusion-Welded-Thirunavukarasu-Murugan/427aa92cc7c7667f92c05434f3704a9c90541ea1

- Navab K, Seyedi Niaki K, Vahdat E, et al. Effect of pressure and deep cryotreatment on the strength of diffusion bonds of St37–1.2542 dissimilar steels. Weld World. 2018. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40194-018-0580-z

- Abdulaziz N, Alhazaa A, Haneklaus N, Almutairi Z. Impulse pressure-assisted diffusion bonding (IPADB): Review and outlook. Metals. 2021;11(2):323. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/met11020323

- Ürkmez N, Yakut R, Alp E. The effects of welding pressure and reinforcement ratio on welding strength in diffusion-bonded AlMg3/SiCp composites. Eur J Technol. 2020. Available from: https://doi.org/10.36222/ejt.686373

- Criado M, Sinha A, Roy J, Ohodnicki N, Tondravi H, Fischer A, Almarza AJ, Kuhn HA, Kumta PN. Understanding the effects of surface finish on diffusion bonding of AZ31 alloys. J Weld Join. 2023. Available from: https://www.e-jwj.org/upload/jwj-2023-41-5-1.pdf

- Andrzejewski H, Badawi KF, Rolland B. The roughness in the diffusion welding of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. Weld J. 1993.

- Wei Y, Zhang S, Jia L, Li Q, Ma M. Study on the influence of surface roughness and temperature on the interface void closure and microstructure evolution of stainless steel diffusion bonding joints. Metals. 2024;14(7):812. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/met14070812

- Ojard GC, Rehbein DK, Buck O. Bond strength evaluation in dissimilar materials. Rev Prog Quant Nondestruct Eval. 1991;10B:1383–1390. Available from: https://dr.lib.iastate.edu/server/api/core/bitstreams/afb9a838-d427-4338-a41f-68a04ba4f7a2/content

- Ohashi O, Hashimoto T. Study on diffusion bonding. J Jpn Soc Mech Eng. 1976;45(8).

- Tensi HM, Wittmann M. Effects of surface finish on the solid state welding of high strength aircraft and aerospace aluminium alloys. In: Solid State Welding of Metals. 1990. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-009-0773-7_27

- Wu GQ, Li ZF, Luo GX, Huang Z. The effects of various finished surfaces on diffusion bonding. Model Simul Mater Sci Eng. 2008;16(8):085006. Available from: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/0965-0393/16/8/085006

- Fitzpatrick G, Broughton T. Diffusion bonding aeroengine components. Def Sci J. 1988;38:477–485. Available from: https://cdn.ymaws.com/titanium.org/resource/resmgr/ZZ-WCTP1988-VOL3/1988_Vol.3-1-V-The_Diffusion.pdf

- Shirzadi A, Wallach E. New method to diffusion bond superalloys. Sci Technol Weld Join. 2004;9:37–40. Available from: https://www.scilit.com/publications/2502d1a042f3e33fa5038f31ca9afd7c

- Ghoshouni AAS, Wallach ER. Surface treatment of oxidizing materials. Washington (DC): Google Patents; 2003. Available from: https://patents.google.com/patent/US6669534B2/en

- Zuruzi AS. Effects of surface roughness on the diffusion bonding of Al alloy 6061 in air. Mater Sci Eng A. 1999;270:244–248. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0921-5093(99)00188-4

- Nami H, Halvaee A, Adgi H. Transient liquid phase diffusion bonding of AlMg2Si metal matrix composite. Mater Des. 2011;32:3957–3965. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matdes.2011.02.003

- Lee YS, Lim CH, Lee CH, Seo KW, Shin SY, Lee CH. Diffusion bonding of Al 6061 alloys using a eutectic reaction of Al-Ag-Cu. Key Eng Mater. 2005;297–300:2772–2777. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4028/0-87849-978-4.2772

- Maity J, Pal TK. Transient liquid-phase diffusion bonding of aluminum metal matrix composite using a mixed Cu-Ni powder interlayer. J Mater Eng Perform. 2012;21:1232–1242. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11665-011-0037-7

- Nami H, Halvaee A, Adgi H, Hadian A. Investigation on microstructure and mechanical properties of diffusion bonded Al/Mg2Si metal matrix composite using copper interlayer. J Mater Process Technol. 2010;210:1282–1289. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2010.03.015

- Shirzadi AA, Wallach ER. Novel method for diffusion bonding superalloys and aluminium alloys. Mater Sci Forum. 2005;502:431–436. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.502.431

- Shirzadi AA, Assadi H, Wallach ER. Interface evolution and bond strength when diffusion bonding materials with stable oxide films. Surf Interface Anal. 2001;31:609–618. Available from: https://www.phase-trans.msm.cam.ac.uk/2005/surface.science.pdf

- Wu F, Zhou WL, Zhao B, Hou HL. Interface microstructure and bond strength of 1420/7B04 composite sheets prepared by diffusion bonding. Rare Met. 2018;7:613–620. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12598-018-1065-3

- Wu F, Zhou W, Han Y, Fu X, Xu Y, Hou H. Effect of alloying elements gradient on solid-state diffusion bonding between aerospace aluminum alloys. Materials. 2018;11:1446. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11081446

- Venugopal S, Seeman M, Seetharaman R, Jayaseelan V. The effect of bonding process parameters on the microstructure and mechanical properties of AA5083 diffusion-bonded joints. Int J Lightweight Mater Manuf. 2022;5(4):555–563. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlmm.2022.07.003

- Chen G, Tan T, Guo Y, Wang H, Liu Y, Pan H. An investigation on diffusion bonding of Mg/Al dissimilar metals using Zn-Bi alloy as interlayer. Mater Lett. 2023;349:134827. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2023.134827

- Wang H, Paidar M, Kumar NK, Seif ElDin HM, Kannan S, et al. Influence of bonding time during diffusion bonding of Ti–6Al–4V to AISI 321 stainless steel on metallurgical and mechanical properties. Vacuum. 2024;222:113072. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacuum.2024.113072

- Venugopal S, Seeman M, Seetharaman R, Jayaseelan V. The effect of bonding process parameters on the microstructure and mechanical properties of AA5083 diffusion-bonded joints. Int J Lightweight Mater Manuf. 2022;5(4):555–563. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlmm.2022.07.003

- Kadhim ZD, Al-Azzawi AI, Al-Janabi SJ. Effect of the diffusion bonding conditions on joints strength. J Eng Sustain Dev. 2009;13(1):179–188. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337209506_Effect_of_the_Diffusion_Bonding_Conditions_on_Joints_Strength

- Lin J, Lei Y, Lu L, Fu H, Guo F. Effect of temperature and zinc coating on interfacial bonding between steel and aluminum dissimilar material. Procedia Manuf. 2019;37:273–278. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2019.12.047

- Negemiya A, Selvarajan R, Sonar T. Effect of diffusion bonding time on microstructure and mechanical properties of dissimilar Ti6Al4V titanium alloy and AISI 304 austenitic stainless steel joints. Mater Test. 2023;65(1):77–86. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1515/mt-2022-0209?urlappend=%3Futm_source%3Dresearchgate.net%26utm_medium%3Darticle

- Suzuki KT, Sato YS, Tokita S. Rapid joining of commercial-purity Ti to 304 stainless steel using Joule heating diffusion bonding: Interfacial microstructure and strength of the dissimilar joint. Metals. 2020;10(12):1689. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/met10121689

- Zhang J, Shang Y, Dong YR, Pei Y, Li S, Gong S. The crack initiation and strengthening mechanism in FGH96 solid-state diffusion bonding joint by quasi-in-situ SEM-DIC and EBSD. Mater Today Commun. 2022. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.103689

- Shu X, Li F, Xuan Z, Tu S, Yu R. Interfacial failure mechanism of 316L stainless steel diffusion bonded joints. 2013. Available from: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Interfacial-Failure-Mechanism-of-316LSS-Diffusion-Li-Xuan/b7b8b3872ce1a745329962605ca68817676ea09e

- Li Y, Li S. Quality evaluation of diffusion bonded joints by electrical resistance measuring and microscopic fatigue testing. Chin J Mech Eng. 2011. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3901/CJME.2011.02.187

- Zhang J, Shang Y, Dong YR, Pei Y, Li S, Gong S. The crack initiation and strengthening mechanism in FGH96 solid-state diffusion bonding joint by quasi-in-situ SEM-DIC and EBSD. Mater Today Commun. 2022. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2022.103689

- Sung H, Kim C, Kim C, Jang J. Diffusion bonding of a cold-worked Ni-base superalloy. 2018. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1115/ETAM2018-6716

- Dong JH, Liu H, Ji SD, Yan DJ, Zhao HX. Diffusion bonding of Al-Mg-Si alloy and 301L stainless steel by friction stir lap welding using a Zn interlayer. Materials. 2022;15(3):696. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15030696

- Chandrappa K, Kumar A, Shubham K. Current trends in diffusion bonding of a titanium alloy to a stainless steel with an aluminium alloy interlayer. 2021. Available from: https://doi.org/10.9734/bpi/aaer/v4/7649D

- Akca E, Gursel A. A review on superalloys and IN718 nickel-based INCONEL superalloy. Period Eng Nat Sci. 2015;3:15–27. Available from: https://doi.org/10.21533/pen.v3i1.43

- Messler RW. Principles of welding: Processes, physics, chemistry, and metallurgy. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/book/10.1002/9783527617487

- Kundu S, Ghosh M, Laik A, Bhanumurthy K, Kale GB, Chatterjee S. Diffusion bonding of commercially pure titanium stainless steel using copper interlayer. Mater Sci Eng A. 2005;407:154–160. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msea.2005.07.010

- Barrena MI, Matesanz L, Gómez de Salazar JM. All2O3/Ti6Al4V diffusion bonding joints using Ag-Cu interlayer. Mater Charact. 2009;60(11):1263–1267. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2009.05.007

- Barrena MI, Gómez de Salazar JM, Merino N, Matesanz L. Characterization of WC-Co/Ti6Al4V diffusion bonding joints using Ag as interlayer. Mater Charact. 2008;59(10):1407–1411. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2007.12.008

- Rahman AHME, Cavalli MN. Diffusion bonding of commercially pure Ni using Cu interlayer. Mater Charact. 2012;69:90–96. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matchar.2012.04.010

- Lin J, Lei Y, Lu L, Fu H, Guo F. Effect of temperature and zinc coating on interfacial bonding between steel and aluminum dissimilar materials. Procedia Manuf. 2019;37:273–278. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2019.12.047

- Zhang Y, Long B, Meng K, Gohkman A, Cui Y, Zhang Z. Diffusion bonding of Q345 steel to zirconium using an aluminum interlayer. J Mater Process Technol. 2020;275:116352. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2019.116352

- Zhang Z, Li J, Liu K, Wang J, Jian S, Xu C, et al. Diffusion bonding, brazing, and resistance welding of zirconium alloys: A review. J Mater Res Technol. 2023. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmrt.2023.07.182

- Hirose A, Matsui F, Imaeda H, Kobayashi KF. Interfacial reaction and strength of dissimilar joints of aluminum alloys to steels for automobile applications. Mater Sci Forum. 2005;475:349–352. Available from: https://doi.org/10.4028/www.scientific.net/MSF.475-479.349